Spiritual Climate of Business Organizations and Its Impact on Customers’ Experience

Ashish Pande

Rajen K. Gupta

A. P. Arora*

Abstract.

This study examines the notion of ‘spirituality’ as a dimension of human self, and its relevance and role in management. Major thesis of this research is that spirituality of employees is reflected in work climate. This may in turn affect the employees’ service to the customers. In the first part of the study a Spiritual Climate Inventory is developed and validated with the data from manufacturing and service sector employees. In the later part, hypothesis of positive impact of spiritual climate on customers’ experience of employees’ service is examined and found to be substantiated empirically.

Introduction

In the midst of dynamic economic forces and technological breakthroughs, business corporations are set to play the lead role in shaping and creating modern society. If the revenues of the governments and the largest corporations are listed together, 77 of the top 100 are corporations (Assadourian, 2006). The top 100 Trans National Corporations alone account for one-tenth of gross world product. With tremendous resources, size, and being embedded in social system, corporations can exert extraordinary influence over the civic, economic, and cultural life of society.

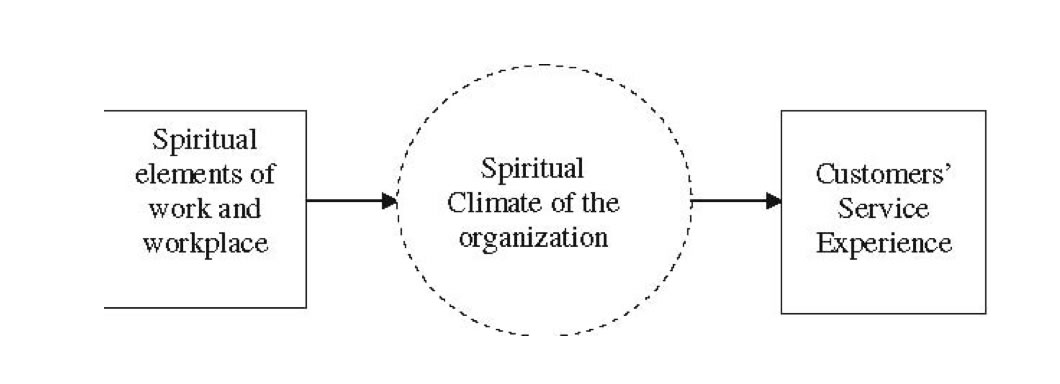

Source of market value of firms is shifting toward more and more intangible resources (Henson, 2003). New sources of competitive advantage are being explored in the form of creativity (Basadur, 1992 ; Woodman et al., 1993), innovation (Cho and Pucik, 2005), tacit knowledge (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995), and, most interestingly, spirituality (Mitroff and Denton, 1999). Suggestion of Mitroff and Denton (1999) about spirituality as the ultimate competitive advantage is based on their observation that now people, as part of their spiritual journey are struggling with what this means for their work. Similarly, Nichols (1994) observed that creating meaning and purpose would be most important managerial task in the 21st century. She emphasized for companies to find ways to harness soul searching on the job, not to just gloss over the matter or merely avoid it. From this realization has come a call for nurturing and integrating all four aspects of human existence – the physical, mental (intellectual), emotional, and spiritual (Moxley, 2000) at work. This study takes forward these notions. Major thesis of this research is that spirituality of employees is reflected in work climate. This may in turn affect the employees’ service to the customers. Figure 1 summarizes this thesis.

Figure 1. Causal model of spiritual climate and its impact.

In light of current status of scientific enquiry in the area of ‘spirituality in management,’ this study is primarily aiming at three things;

- to trace the conceptual underpinnings of notion of spirituality in different streams of knowledge particularly relevant in management

- to develop and validate an instrument to measure spirituality in organization climate and

- to empirically test the impact of spiritual climate on customers’ experience of employees’ service

With these objectives in view first we describe the conceptual and theoretical foundation of spirituality presented in social science streams of ‘well-being’ and ‘positive psychology.’ Second, we show the connection of positive psychology and positive organizational behavior and relevance of spirituality in this stream of scholarship. Third, we identify the conceptual convergence in the ‘spirituality in management’ and report the existing state of research in this field. Fourth, we describe how spirituality in management can be conceptualized as spiritual climate at workplace. Fifth, relationship of spiritual climate and its impact on customers was hypothesized. Sixth, the process and findings of developing and validating the construct of spiritual climate and testing of hypotheses one described. We conclude by discussing nature of construct and hypothesized relationship, theoretical implication of this work, and limitations of this study.

Conceptual and theoretical foundation

Human personality and its functioning are studied in human wellness stream. ‘Human Wellness’ literature conceptualizes human functioning as body (soma), soul (psyche) and spirit (pneuma). In the humanism school1 of ‘wellness,’ human functioning is viewed as a synthesized whole, and each component is seen as inextricably interrelated with the other components (Addis, 1995). Theorists in the field of well-being (Bensley, 1991 ; Dunn, 1961) believed that the spiritual dimension is an innate component of human functioning that acts to integrate the other components. Within this philosophical framework, spiritual functioning has equal relevance to the physical, mental, and emotional functioning; one cannot treat an illness or disturbance with one component without understanding the balance and interaction between all the components. Spiritual wellness represents the openness to the spiritual dimension. This openness permits the integration of one’s spirituality with the other dimensions of life, thus maximizing the potential for growth and self-actualization. Charlene (1996) deciphers the four components of spiritual wellness –

1. meaning and purpose in life, 2. intrinsic values, 3. transcendent beliefs/experience, and 4. community/ relationship.

Many authors, thinkers, and researchers (e.g., Frankl, 1978 ; Maslow, 1971) in the field of positive psychology have written about one or more of these factors. The following section briefly reviews the notion of some of prominent psychologists about the spiritual aspect of human personality.

Spirituality in the positive psychology

Jung viewed religion and spirituality as reflective of the soul and did not discard them as delusion and distorting as Freud did.2 Religious ideas and experiences are psychically real, fundamental to human experience, and represent psychic evolution for Jung. Psychological problems are essentially religious problems for him. Jung said:

A psychoneurosis must be understood, ultimately, as the suffering of a soul which has not discovered its meaning … the cause of the suffering is spiritual stagnation or psychic sterility. (Jung, 1978).

Jung (1978) contended that without an ‘‘inner transcendent experience’’ human beings lack the resources to withstand the ‘‘blandishments of the world’’and get in touch with purity of their self (emphasis and explanation added). Jung thought that neither intellectual nor moral insight alone was sufficient and he found that for his patients over age 35 the real problem was finding a spiritual perspective (Jung, 1933).

In the later twentieth century Freudian views were seriously challenged by humanistic psychologists. Taking the ‘potential view’ of human psyche, most of the humanistic or positive psychologists indicated the tendencies of self-development, reflection, and transcendence in human beings. In his work ‘‘On Becoming Person’’ Roger (1961) expressed his belief about people having basically positive direction toward their true being and the human power to reflect and transcend in ‘fully functioning personality’ and flourish in the right condition.

In the same vein Frankl (1978) in his book ‘‘The Unheard Cry for Meaning’’ recognized that the search for meaning is a vital avenue of human development. Views of Fromm (2003) are particularly important because he examined the human development issues in the larger economic, social, and cultural context. According to him humanistic alternatives of development are only a matter of awareness of human being. Describing the path of development for mankind in his book ‘‘The Search for a Humanistic Alternative’’ he wrote that:

In this frame (humanistic development frame) of reference the goal of life is the fullest development of human powers, specifically those of reason and of love, including the transcending of the narrowness of one’s ego.

Maslow (1968 , 1971 , 1996) expressed his human development views referring to the ‘being values’ like wholeness, goodness, self-sufficiency, etc. He considered these values as part of the human self. These being-values are not deficiency-needs. These are meta-needs or growth-needs with which we can never get bored. This is in direct contrast to the basic needs, which can definitely satisfy. Under good conditions people can integrate these values in daily life. Maslow (1971)described such integration in terms of the transcendent self-actualization. For him, transcendent self-actualization carries a spiritual significance and manifests in the recognition of the sacred in life.

Positive organizational scholarship and spirituality

Complementary effort that draws on positive psychology is positive organizational scholarship or better known as positive organizational behavior (POB). Luthans and Church (2002) defines POB as ‘‘the study and application of positively oriented human resource strengths and psychology capacities that can be measured, developed and effectively managed for performance improvement in today’s workplace.’’ POB carves an agenda for how a focus on the positive opens up new and important ways of seeing and understanding organizations (Roberts, 2006). In recent years many studies are conducted on human tendency of self-growth and ego transcendence and its positive relation to mental health (Payne et al., 1990 ; Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), creativity (Larson, 2000), and learning (Howard, 2002 ; Senge et al., 2005). In organizational studies, there has been a growing interest in applying the principles and methodology of positive scholarship to micro-and macro-level organizational issues (Roberts, 2006).

Notions of spirituality as intrinsic drive and motivation to seek meaning in life and place in larger schema of existence are well established in the field of positive psychology and in many other disciplines in the social and natural sciences (Fry, 2003). Spirituality being an aspect of human potential which is also defined as highest reaches of human development (Wilber, 2004) is apt to be part of positive organizational scholarship.

A note on spirituality in wisdom traditions

Most of the wisdom traditions in the world have shown concern for spirituality. Vedanta, Confucian, Buddhists, Christian, Islam all have emphasized the importance of nurturing the spiritual aspect of human being. The importance of these traditions lies in the fact that these were based on both philosophical and experiential pillars. In the form of meditation, Prayer, Zen, or Yoga, these traditions have produced many time-tested experiential methods to experience the spirituality.

The contemporary understanding of spirituality and its role in management is in line with the traditionalVedic literature.Vedanta3 teaches that ‘‘truth’’ has two meanings;Dharma andRta (Bhattacharyya, 1995).Dharma is that which sustains all beings, according to their own nature and is in harmony with each other.Bhagwad Gita,4 teachesthat, to discover and to follow the self-dharma (Swadharma) is the ideal of human life. One never becomes tired of one’s Swadharma. One’s Swadharma gives one maximum satisfaction and joy and finally leads to making the mind quiet and still. Work, which leads to agitation, is not Swadharma.

The second meaning for ‘‘truth’’ in the Vedic literature is Rta. This aspect is termed as the ‘‘unseen order of things.’’ It is the eternal path of divine righteousness for all beings, both humans and deities. The order must be followed to maintain the world order. Experience of Rta is termed as ego transcendence or expansion of awareness. According to Bhagawad Gita, in the ordinary vocations of life Rta may manifest as Loksangrah, i.e., ‘‘working for world maintenance’’ or performing one’s job with intent of welfare of larger social and natural environment. Thus, ‘Swadharma’ and ‘Loksangrah’ are the two constructs to contemporary thoughts about spirituality.

Review of thoughts of human wellness, positive psychology, and its relation with positive organizational behavior gives the foundational understanding of spirituality in management. Our understanding of spirituality in management and its conceptualization as spiritual climate at workplace is informed and validated through these knowledge streams. The upcoming section focuses on existing literature on spirituality in management.

Spirituality in management

Management academics had never been totally blind to spiritual perspective of work. Quatro (2004) posited this point referring to the writings of Follett (1918)5 in the classical management literature. Weber (1958) also called for developing the management theories and practices de-emphasizing materialism and individualism. In 1997 Academy of Management (USA) setup an interest group on spirituality and religion at workplace. Many academic journals like the Journal of Management Education (2005, 2006), Journal of Organizational Change Management (1999, 2002), Leadership Quarterly (2005), Organization (2004), Journal of Social Economics (1996, 1998), Pfeiffer annual of training and consulting (2004), etc. have brought special issues or published articles on different aspects of spirituality. Many terms like divinity, soul, ‘managing with love’ and ‘rediscovering the soul’ have started appearing in contemporary management academic and popular literature. Academic management researchers, management consultants and gurus, and practicing CEO’s have all written about it. Corporate spirituality may well shape the organization of the future (Zohar and Marshall, 2004). Organizations and groups like ‘Spirit at Work’ (www.spiritatwork.org) and Global Dharma Centre (www.globaldharma.com) are tirelessly propagating the ideas of spirituality at work for last many years in different parts of America, Europe, and Asia.

Spirituality at workplace: the conceptual convergence

Thompson (2001) denotes that spirituality at workplace has to do with how you feel about your work whether it is a job or a calling. Sanders et al. (2004) define spirituality in the workplace as the extent to which the organization encourages a sense of meaning and interconnectedness among their employees. Sheep (2004) defines spirituality at workplace through four components: self-workplace integration, meaning in work, transcendence of self, and personal growth of one’s inner life at work. Other than definingspiritualitycertain studies (Lips-Wiersma, 2003 ; McCormick, 1994) identify the underlying themes in spirituality in management literature. Viewing the fundamental conceptualization of spirituality and definitions given in contemporary literature indicate that spirituality is a multi-dimensional, multi-level phenomenon. Acknowledging that consensus is lacking among spirituality literature on how spirituality should be defined (Ashforth and Pratt, 2003 ; Benefiel, 2003) we nonetheless propose that a conceptual convergence can be traced in the workplace spirituality literature; harmony with self, harmony in social and natural environment and transcendence. Having relational aspect more pronounced feministic view of spirituality also involve these three aspects (Fischer, 1988 ; Harris, 1989). Spirituality in management is a dynamic balance of these three factors.

Harmony with self

Organizations are sites where individuals find meaning for themselves and have their meaning shaped (Fineman, 1993 in Dehler and Welsh, 1994). Dehler and Welsh (1994) proposed that spirituality in organizations represents a specific form of work feeling that energizes the actions. This aspect refers to individuals’ alignment to the work. It is about finding meaning and purpose in work (Ashmosh and Duchon, 2000 ; Fry, 2003; Milliman et al., 2001; Mitroff and Denton, 1999 ; Sheep, 2004 ; Quatro, 2004). This observation is parallel to the notion ofSwadharma explained earlier. Variables like the quest for feeling good (Morgan, 1993), a profound feeling of well-being, and joy at work (Kinjerski, 2004) also indicate the underlying theme of ‘harmony with self’ at work. Inner life at work, self actualization (Ashforth and Pratt, 2003 ; Giacalone and Jurkiewicz, 2003 ; Pfeffer, 2003), or development of one’s full potential (KrishnaKumar and Neck, 2002) represents this aspect of literature.

Harmony in work environment

Second dimension of spirituality as literature suggests is relational. This is manifested in relation with social and natural environment. This spiritual dimension is manifested through sense of community (Ashmosh and Duchon, 2000), being comfortable with the world (Morgan, 1993), work place integration, connectedness (Ingersoll, 2003), compassion (McCormick, 1994), respect, humility and courage (Heaton et al., 2004) common purpose, (Kinjerski and Skrypnek, 2004), inclusiveness and interconnectedness (Kinjerski and Skrypnek, 2004 ; Marcqus et al., 2005). This aspect of spirituality in management is reflected in greater kindness and fairness and industrial democracy (Biberman and Whitty, 1997) and shared responsibility (Marques, 2005).

Transcendence: the underlying aspect

In the management literature transcendental aspect is related to ‘connection to something greater than oneself’ (Ashforth and Pratt, 2003 ; Dehler and Welsh, 1994; Sheep, 2004). Ashforth and Pratt (2003) explain that the ‘‘something’’ can be ‘‘other people, cause, nature, or a belief in a higher power.’’ McCormick (1994) talks about meditative work and describes it as experience of being absorbed in work, losing any sense of self, and becoming one with the activity. Mirvis (1997) explains that ‘individual self’ can transcend in four concentric circles of consciousness (1) consciousness of self; (2) consciousness of others; (3) group consciousness; (4) to organize in harmony with the unseen order of things. This explanation and observation is comparable with the notion of Rta explained earlier. Mirvis (1997) explained that transcendence at workplace results in ‘‘company as community’’ and wrote that ‘‘Community is built upon transcendence of human differences rather than commonalities.’’ Transcendence results in employees to rise above traditionally divisive boundaries of hierarchy, demography, or even spiritual orientation, etc. (Sheep, 2004).

Impact of spirituality in organization

Impact of spirituality in the business organization has been studied in terms of job behavior of the employees and overall organizational performance. The literature correlating workplace spirituality related factors with employees’ job behavior converge into three areas; motivation, commitment, and adaptability (Jurkiewicz and Giacalone, 2004). Study of Scott (2002) demonstrated that organizations high on spiritual values, outperform those without it, on the parameters of growth, efficiencies, and returns on investments than those without it. Nur (2003)in his doctoral research work reported that organizations managed by spiritual virtues (MBV’s) earned better returns in the duration of 5 years. Colvin (2006) in his analysis (in Fortune magazine) of ‘Best Places to Work’ in USA though does not use the word spirituality but writes that these are the places where people find a purpose to work other than their pay checks. Meta analysis of Dent et al. (2005) showed the positive association of spirituality and productivity. Marques (2005) suggested that spirituality results in unified pleasant performance and quality orientation of workforce which in turn result in excellent output and community orientation.

Figure 2 summarizes the discussion till now and schematically represents the theoretical and conceptual foundation, conceptual convergence, and impact of spirituality in management.

| Conceptual Underpinning of Spirituality |

Spirituality |

Impact of Spirituality |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Contemporary Thoughts •Positive/ Humanist Psychology •Well-being Literature Positive organizational behavior Traditional Indian Thoughts Swadharma |

Harmony with Self Harmony in Environment

|

Job Behavior Organization

Performance |

|

Figure 2. Schematic representation of spirituality in management literature (Source: Pandey and Gupta, 2008).

Research gap

Review of the relevant literature showed that spirituality at workplace is reflected in the culture and climate. Literature also incorporates the linkage between spirituality at workplace and certain job behaviors of employees which in turn affect the organizational performance. Our review suggests that conceptualization of spirituality and related constructs is a foundational requirement for better theorizing in the field of spirituality in management. Potential contribution of wisdom traditions is acknowledged in the literature at many places but the systematic attempts of examining and integrating this with contemporary thinking are few in number. Predictive studies examining association of spirituality with organizational performance outcome are very few. Marques (2005) indicates the ‘quality orientation’ of employees as one of the outcomes of spirituality in organizations without providing the empirical support for his claim. Moreover, most of the studies in the literature are ‘with-in organization’ studies which are likely suffering from ‘same source bias.’

Developing the construct of spiritual climate at workplace

Workplace spirituality is intended to provide a means for individuals to integrate their work and their spirituality, which will provide them with direction, connectedness, and wholeness at work. Spirituality is reflected in the values framework of the organization (Jurkiewicz and Giacalone, 2004) and values are reflected in organizational climate. Hence, concept of work climate may be a promising mechanism for understanding spirituality at workplace.

A work climate is defined as perceptions that are psychologically meaningful descriptions that people can agree characterize a system (Schneider, 1975). The majority of the climate types are aggregation of perceptions of organization (Victor and Cullen, 1988). The prevailing perception about the work and immediate work group that have spiritual content constitute the spiritual climate. Like most of the other climate research this is also grounded in the Gestalt psychology of Kurt Lewin. Organizational Climate is a gestalt – ‘whole’ – that is based on perceived patterns in the specific experiences and behaviors of people in organization. Broad definition of spirituality is employed in developing the construct of spiritual climate that is general and pervasive characteristics of work group and defined as:

the collective perception of the employee about the workplace that facilitates harmony with ‘self’ through meaningful work, transcendence from the limited ‘self’ and operates in harmony with social and natural environment having sense of interconnectedness within it.

Variables of spiritual climate of business organization

Based on the literature presented above and opinion of experts, following variables of spirituality in organization are identified. These variables cover the three conceptually converging streams being identified in the ‘spirituality in management’ literature and their parallel notions in the Vedantic literature. The variables of meaningful work, hopefulness, and authenticity are related to harmony with self. Sense of community and respect for diversity are related to harmony in work environment and meditative work, and Loksangrah are related to transcendence aspect of workplace spirituality (Table I).

TABLE I Representation of spiritual climate variables

Dimensions in contemporary literature |

Sub-constructs |

Harmony with self |

•Meaningful work |

| Harmony in environment |

•Respect for diversity |

| Transcendence |

(Concern for social and natural environment) |

- Meaningful work: Work for life not only for livelihood (Ashmos and Duchon, 2000).

- Hopefulness: Individual determination that goals can be achieved and belief that successful plans can be formulated and pathways can be identified to attain the goal (Snyder, 2000).

- Authenticity: Alignment of people’s actions and behaviors with their core, internalized values and beliefs (Pareek, 2002).

- Sense of community: Experience of interconnectedness and interdependence of employees (Jurkiewicz and Giacalone, 2004).

- Loksangrah: Working for world maintenance (Radhakrishnan, 1951); Concern for social and natural environment.

- Respect for diversity: Adapting a plural way of accommodating the multiplicities and diversities of societies and individuals and operates on shared opportunity and shared responsibility (Zohar, 2004).

- Meditative work: Experience of being absorbed in work, losing sense of self, and becoming one with the activity (McCormick, 1994).

Distinguishing spiritual climate from related constructs

As part of our conceptual development of spiritual climate construct, we distinguish it from related constructs of employees’ engagement, ethical climate, and service climate.

First, engagement is similar to spiritual climate in that it refers to deeper involvement in work and a feeling of connectedness at workplace. However, engagement and spiritual climate have important differences in terms of level of construct and contributing factors of the construct. First, employees’ engagement (of which Q12 is the most widely used assessment tool) covers both individual level variables like role clarity and learning opportunity. It also covers dyadic level construct like appreciation and collective level construct, i.e., enabling environment, whereas spiritual climate is purely a collective level construct. Second, sense of contribution to the larger social and natural environment, authenticity, meaningful work are constituting variables of the spiritual climate which are not the part of employees’ engagement construct.

Spiritual climate is distinct from ethical environment also. Ethical climate typically involves rule, law, and code along with caring and independence (Victor and Cullen, 1988). Similar to spiritual climate ethical climate involves caring but the scope of spiritual climate construct put it close to the spiritual aspects of workplace unlike ethical climate which focuses on ethical temperament of people creating the organizational climate.

Spiritual climate is also conceptually distinct from service climate (Schneider, 1994). Service climate captures the managerial behavior and branch administration, whereas, spiritual climate goes beyond the behavior and captures both employees’ experience of work and work group and does not include administrative aspects.

Spiritual climate construct is also distinct from ‘spirituality in management’ construct proposed by Ashmos and Duchon (2000). Like spiritual climate construct spirituality in management involves inner life, sense of community, and meaningful work. However, conceptualizing spirituality at workplace as climatic construct and inclusion of Loksangrah, (concern for social and natural environment), authenticity, concern for family extend the scope of the construct from its existing conceptualization proposed by Ashmos and Duchon (2000).

Spiritual climate of the organization and customers’ service experience: hypothesizing relationship

Service satisfaction is a function of consumers’ experiences and reactions to a provider’s behavior during the service encounter and service setting6 (Nicholls et al., 1998). Every service organization routinely experiences opportunities to personally interact with their customers through their employees. Lack of concreteness of many services increase the criticality of employee service in the formation of customers’ perception about service quality (Crosby et al., 1990). Thus, behavior of the employee plays an important role in shaping the customer’s perception of service quality (Crosby, 1990) which in turn affects the future consumption behavior (Chandon et al., 1997).

Chatman and Barsade (1995) suggest that behavior is a function of characteristics of the person and environment. There has been increasing awareness of the impact of organizational climate on employee behaviors. Studies examining specific dimensions of climate, such as innovation climate (Anderson and West, 1998), safety climate (Hofmann and Stetzer, 1996), and transfer of training climate (Tracey et al., 1995) have explained significant variance in specific employees’ behaviors. In the same way current study examines impact of spiritual climate of the workplace on employees’ service performance.

Literature review suggested that spirituality at workplace makes the employees motivated, adaptable, and committed to their work. These qualities of employees should logically be reflected in service encounters. ‘Moments of truth’ are created is these encounters (Carlzon, 1997). During these encounters, the customer is mentally evaluating the service they are experiencing and forming a lasting opinion about organization. Additionally, Marques (2005) suggested that spirituality at workplace results in unified pleasant performance and quality orientation of workforce. Other things being equal employees working in spiritual climate are more likely to provide better service experience to the customers. Hence, we proposed the following relationships between customer experience and spiritual climate of the organization.

H1: Workplace showing higher Spiritual climate is experienced by the customers as providing better employees’ service.

Following sub-hypotheses are proposed based on different aspects of spiritual climate:

H1a: Customers experience better employees’ service in the workplace where employees’ find their work meaningful.

H1b: Customers experience better employees’ service in the workplace where employees’ experience sense of community.

H1c: Customers experience better employees’ service in the workplace where employees are concerned about each other families.

H1d: Customers experience better employees’ service in the workplace where employees perceive authenticity in behavior at work place.

H1e: Customers experience better employees’ service in the workplace where employees work with a feeling of Loksangrah, i.e., as if they are working for world-maintenance.

H1f: Customers find better employees’ service in the workplace where employees experience meditative work at the work place.

Research design

This study is based on the positivist paradigm of social science. Deductive procedure of falsifying hypotheses is adopted as cognition process. Two constructs between which a positive relationship is proposed are assumed to be constituted of several sub-constructs or variables. The design involved developing the scale of spiritual climate, examining the validity of constructs of spiritual climate and customers’ experience of employees’ service and testing the hypotheses.

Spiritual climate is collective (macro) level construct. Its outcome, i.e., customers’ service experiences is also a collective construct because customers in general experience the whole branch instead of single interaction. Being a macro-level study, unit of observation was the work group, i.e., branch of the public sector bank. Questionnaire-based cross-sectional survey design was used to collect data from employees of the branch and their respective customers. Overview of the empirical study is shown in Figure 3 .

The study was conducted in two phases. First phase was focused on developing the scale of spiritual climate in organization through exploratory factor analysis. Second phase of the study aimed at validating the spiritual climate inventory and testing the hypothesized relationship between spiritual climate and its impact on customers’ experience.

Figure 3. Flow chart of empirical research.

Data from the employees of manufacturing sector were used for exploratory factor analysis. This choice was justified based on the theory which suggests that core spiritual concerns remain same in different walks of life (Maslow, 1996). Data of 162 executives from Indian public sector firms were used for scale development. Second phase of study was conducted in 31 branches of a large public sector bank chosen with multi-stage stratified random sampling.

Development and validation of spiritual climate inventory

Theory-driven (construct-oriented) approach was adopted for scale development of spiritual climate. Sub-construct and related items were decided based on review of empirical, philosophical and spiritual literature. Perception about the work and work environment amongst organizational members were collected on Likert type scale format to assess the spiritual climate of the organization. Development of the ‘Spiritual climate’ inventory was completed in three major steps:

- Item creation,

- Validity check, and

- Reliability testing.

A battery of 120 items was created based on operational definitions of the above-mentioned variables. Construct and sub-constructs were taken through test of face and content validity resulting in total 78 items. The spiritual climate items were further screened for appropriateness by use of mainly two procedures: Q-sorting and item evaluation. This list of items was further subjected to qualitative analysis based on cognitive interviewing of six potential respondents which resulted in further reduction of items to 56. First pilot testing based on quantitative analysis of the instrument was conducted on the data of 76 respondents. Items related to sub-construct of hopefulness, and respect for diversity showed high correlation with the items of other sub-constructs thus were dropped from further analysis. Since we do not have any theoretical or intuitive reason to justifiably disbelieve correlation amongst the factors, we have chosen direct oblimin rotation which is oblique (non-orthogonal) in nature. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) statistics, the sampling adequacy was decided to be predicts 60 or higher to proceed with factor analysis. For item loading, the rule-of-thumb is that loadings is ‘‘weak’’ if less than 0.4, ‘‘strong’’ if more than 0.6, and otherwise is ‘‘moderate.’’

Revised and shortened inventory was administered on a sample of 162 respondents and was subjected to exploratory factor analysis. After careful assessment of the items based on the above criterion, we finally reached to the seven-factor solution. Factor loading of the different items on respective factors are given in Table II.

Seven-factor solution was obtained through EFA. Based on the criterion explained above, the following items finally constituted the spiritual climate inventory (Table II).

As mentioned above the non-orthogonal rotation gave the seven-factor solution. Factors emerging in this stage were quiet similar to what were hypothesized theoretically in the study. These factors were related to meaningful work, two factors of sense of community, two factors related to loksangrah and meditative work. KMO and Bartlett test value was 0.775 and Cronbach’s alfa was 0.873. Value of Chi square test (371.988) at 231 degrees of freedom was significant at less than 0.01 level of significance. The instrument was explaining approximately 72% variance in the given sample. Value of Cronbach’s alfa for the different sub-constructs was between 0.91 and 0.74 indicating the reliability of the scale.

TABLE II List of items and respective loadings

| S. No. |

Items |

Loading |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

My job helps me to understand my life’s purpose |

0.699 |

| 2 |

Working here makes my life meaningful |

0.881 |

| 3 |

I work here for money; otherwise there is nothing else for my life here. (reverse) |

-0.787 |

| 4 |

Working for me here is like puja – a means for realizing my real self |

0.661 |

| 5 |

People help each other in family matters |

0.898 |

| 6 |

People here are concerned toward each others’ family responsibilities |

0.952 |

| 7 |

When stuck with a problem people feel free to ask for: |

|

| a. advice from their colleagues |

0.760 |

|

| b. advice from superior |

0.843 |

|

| c. help from their superior |

0.735 |

|

| d. help from colleagues |

0.789 |

|

| 8 |

People here try to avoid wastage of any kind (paper, electricity, etc.) |

0.384 |

| 9 |

People are concerned about the natural environment while working here |

0.536 |

| 10 |

People here perform their duties as if it contributes to: |

|

| a. the community |

0.855 |

|

| b. the larger society |

0.889 |

|

| c. the mankind |

0.895 |

|

| 11 |

Work itself is like an enjoyment for me |

0.882 |

| 12 |

I am deeply involved in my work here |

0.814 |

| 13 |

I feel frustrated after working here |

-0.777 |

| 14 |

People in the branch are what they appear to be |

0.795 |

| 15 |

Peoples’ actions here are aligned with their words |

0.908 |

| 16 |

People own up to mistakes with each other in the branch |

0.866 |

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the spiritual climate inventory

The second phase of the study was conducted in 31 branches of a public sector bank. In the two branches the number of respondent employees was less than one-third of the total employees present in the branch. In another branch Core Banking System (CBS) and online banking features remained halted due to some technical problem. This resulted in lot of anxiety among both the customers and the employees. In this situation their perceptions were subjected to be tinted with immediate circumstances. Hence, the data from these branches were not used in the final analysis and eventually response from the employees and customers of 28 branches was subjected to further analysis in this stage. Overall 39.2% officers and 60.8% clerical staff were amongst respondents. More than 80% respondents were in the age of 40s and 50s which made the average age of employees 47.2 years. Percentage of female employees amongst the respondents was 26.6%. More than 85% of total employees respondents had been primarily socialized in northern India (i.e., Delhi, Haryana, UP, and Punjab) with the highest percentage (68%) coming from Delhi.

The data relating to this scale was subjected to confirmatory factor analysis. CFA seeks to determine if the number of factors and the loadings of measured (indicator) variables on them conform to what is expected on the basis of pre-established findings. Indicator variables are selected on the basis of result of exploratory factor analysis. CFA is used to see if they load as predicted on the expected number of factors. CFA can be performed in two ways: traditional method and through Structure Equation Modeling. For CFA one uses principle axis factoring (PAF) rather than principle components analysis (PCA) as the type of factoring.7 Factor (as from principal axis factoring, a.k.a. common factor analysis) represents the common variance of variables, excluding unique variance, and is thus a correlation-focused approach seeking to reproduce the inter-correlation among the variables. This can provide a more detailed insight into the measurement model than can the use of single-coefficient goodness of fit measures used in the SEM approach. Criteria related to factor loading and cross-loading of items across factor, eigen value, KMO, and Chi square test for goodness of fit remained same as that for EFA. Oblique rotation was opted for the analysis. Standard deviation and item loading in the pattern matrix8 are given in the following table (Table III).

CFA gave the five-factor solution for the spiritual climate scale. Items related to the ‘meditative work’ and ‘concern for natural environment’ did not show the discriminant validity. (These findings are further explained in discussion section). Value of KMO and Bartlett of the scale was 0.776 and Cronbach alfa was 0.883 suggesting the reliability of the scale. The scale explained about 58% variance (Annexure).

‘Spiritual climate at work’ as a construct has some conceptual similarity with supportive environment. Based on the study of Kalra (1997) three item scale on supportive environment was designed. Correlation of the spiritual climate scale with supportive environment scale was 0.728 showing the convergent validity of the scale. Discriminant validity of the construct is evident by negative loading of reverse items and their negative correlation with the other items in the inventory in both the stages of empirical testing. This shows that construct under research is empirically distinguishable from the conceptually opposite construct.

TABLE III Items and their respective leading in different factors (banking sector)

Loading |

||||||||

| S. No. | Items | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 | My job helps me to understand my life's purpose. | 0.699 | ||||||

| 2 | Working here makes my life meaningful. | 0.881 | ||||||

| 3 | I work here for money; otherwise there is nothing else for my life here. (reverse) | -0.787 | ||||||

| 4 | Working for me here is like puja: a means for realizing my real self. | 0.661 | ||||||

| 5 | People help each other in family matters. | 0.898 | ||||||

| 6 | People here are concerned towards each others' family responsibilities. | 0.952 | ||||||

| 7 | When stuck with a problem people feel free to ask for: | |||||||

| a. advice from their colleagues | 0.760 | |||||||

| b. advice from superior | 0.843 | |||||||

| c. help from their superior | 0.735 | |||||||

| d. help from colleague | 0.789 | |||||||

| 8 | People here try to avoid wastage of any kind (paper, electricity etc.) | 0.384 | ||||||

| 9 | People are concerned about the natural environment while working here. | 0.536 | ||||||

| 10 | People here perform their duties as if it contributes to: | |||||||

| a. the community | 0.855 | |||||||

| b. the larger society | 0.889 | |||||||

| c. the mankind | 0.895 | |||||||

| 11 | Work itself is like an enjoyment for me. | 0.882 | ||||||

| 12 | I deeply involved in my work here. | 0.814 | ||||||

| 13 | I feel frustrated after working here. | -0.777 | ||||||

| 14 | People in the branch are what they appear to be. | 0.795 | ||||||

| 15 | Peoples' actions here are aligned with their words. | 0.908 | ||||||

| 16 | People own up to mistakes with each other in the branch. | 0.866 | ||||||

Customers’ service experience: nature of the construct

As mentioned above the logic of Grace and O’Cass (2004) was followed in this study where he described the three contributing factors of service experience, i.e., core service, Servicescape, and employees’ service. The factor employees’ service is a function of variables like Prompt Service, Helpfulness, Availability, Trust, Safety, Politeness, Understanding behavior, Personal, attention, Being well informed, and Keeping promise. Questions were like ‘Employees in this branch give prompt service,’ ‘Employees in this branch are polite’, etc. Customers responses were collected on Likert type (1–5) scale based on these variables.

Responses from randomly chosen 15–20 customers were collected from each branch. Data of 462 customers from 28 branches were used for the study. Given the conceptualization of the construct and its background these variables were hypothesized to be fallen in single factor. But survey result suggested that these variables are clubbed in two factors as shown in Table IV Trust and safety related variables were clubbed in second factor, whereas rest of the other variables were clubbed in first factor explaining major portion of variance. Field experience suggested that being a government-owned public sector bank customers had obvious feeling of trust and safety while interacting and doing transaction. So, the customers’ perception about these two variables was like that of ‘given’ or taken for granted, whereas for responses collected about other employees’ service variables were more specific, stronger, and varied. Further analysis was conducted on the average score on customers’ experience excluding the scores on these two variables. Output of factor Analysis results are given in Table IV .

Factor loading of different items of Employees Service

Scale

| Pattern Matrix(a) |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Factor |

||

|

1 |

2 |

|

|

Promptserv1 |

0.751 |

0.057 |

|

helful2 |

0.806 |

0.028 |

|

notbusi3 |

0.726 |

0.066 |

|

trust4 |

0.089 |

0.770 |

|

safe5 |

-0.04 |

0.786 |

|

polit6 |

0.807 |

-0.076 |

|

undrstdnid7 |

0.779 |

0.04 |

|

peratensn8 |

0.796 |

-0.045 |

|

info9 |

0.678 |

0.059 |

|

kipromis10 |

0.721 |

-0.047 |

The value of KMO and Bartlett’s test was found 0.923 and Reliability coefficient (Cronbach alfa) was 0.91.

Testing hypotheses

Second phase of the study aimed at falsification of hypothesized relationship between spiritual climate and customers’ service experience having spiritual climate as antecedent and customer’ service experience as the consequent. Testing the adequacy of the relationship element of proposition was based on two major criteria; logical adequacy and empirical adequacy. Logical adequacy is defined as the implicit or explicit logic embedded in the hypotheses and propositions which ensure that the hypotheses and propositions are capable of being disconfirmed (Bacharach, 1989). To ensure the logical adequacy of the proposed relationship, nature of antecedents and consequents are specified. Respondents of antecedent (spirituality in organization) are employees of the branches, whereas respondents for consequent variable (service experience) are the customers of the particular branch.

Empirical adequacy criterion is when there is either more than one object of analysis or those objects of analysis exist at more than one point of time. In order to meet this criterion, variability in nature of branches of the bank was ensured while collecting data. Predictive adequacy of propositions was checked by administering standardized spirituality at workplace questionnaire and its association of combined score of customers’ service experience.Schneider (1987) states that it is employees’ behaviors that make organizations what they are. Drexler (1977) and Schneider (1987) argue for the validity of using employee perception to measure organizational (collective) level characteristics. Based on these recommendations average scores of spiritual climate and employees’ service of 28 branches were used to test the hypothesis. In order to check the strength of causality regression analysis was performed on these scores. Summary of regression model is given below:

| Model | R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | Std. error of the estimate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

0.411 |

0.169 |

0.137 |

0.19588 |

||||

Model |

Change statistics |

Durbin-Watson | ||||||

| R2 Change |

F Change |

df1 |

df2 |

Sig. F Change |

||||

| 1 |

0.169 | 5.276 |

1 |

26 |

0.030 |

1.691 |

||

The Model Summary table in SPSS output, shown above, gives R, R2, adjusted R2, the standard error of estimate (SEE), F change and corresponding significance level, and the Durbin-Watson statistic. In the regression model above, customers’ experience of employees’ service is predicted from spiritual climate.

This output shows that spiritual climate explains only 16.9% of the variance in customer service experience for this sample. R2 is close to adjusted R2 because there is only one independent variable. R2 change is the same as R2 because the variables were entered at the same time (not stepwise or in blocks), so there is only one regression model to report, and R2 change is change from the intercept-only model, which is also what R2 is. Since there is only one model, ‘‘Sig F Change’’ is the overall significance of the model. Significant F statistics indicate the overall significance of the model.

The Durbin-Watson statistic is a test to see if the assumption of independent observations is met, which is the same as testing to see if autocorrelation is present. As a rule of thumb, a Durbin–Watson statistic in the range of 1.5–2.5 means the researcher may reject the notion that data are autocorrelated (serially dependent) and instead may assume independence of observations, as is the case here.

Correlation between average scores of spiritual climate of the branches and their respective average customers’ service experience was 0.41 at the p value of 0.03.

Pearson’s r 2 is the percent of variance in the dependent explained by the given independent when (unlike the beta weights) all other independents are allowed to vary. The result is that the magnitude of r 2 reflects not only the unique covariance it shares with the dependent, but also the uncontrolled effects on the dependent attributable to covariance the given independent shares with other independents in the model. Correlation score also supports the positive direction of the hypothesized relationship but does not reflect strong relationship between spiritual climate and customers’ service experience.

Findings of regression and correlation suggested that linear relationship between spiritual climate of the branches and customers’ experience of employees’ service though cannot be denied are not very strong at the same time. In order to clearly examine the impact of spiritual climate and employees’ service we did further statistical analysis, i.e., t-test and Analysis of Variance, which are more sensitive and can bring out the difference in employees’ service scores corresponding to spiritual climate scores more clearly.

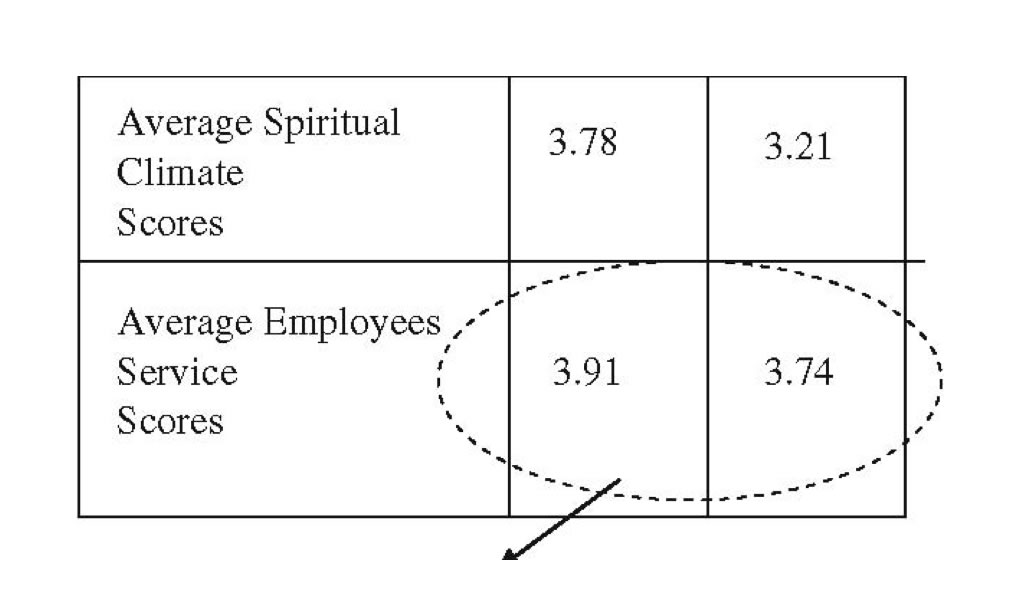

Branches were classified as low and high based on spiritual climate scores. Fourteen branches in each category were identified (Table V).

The average employees’ services scores of corresponding branches were compared through t-test. Difference was found to be significant at p values less than 0.05 (Table VI).

TABLE V Average scores

| No. | Higher Spiritual Climate Scores | Respective Employees’ Service Scores | Lower Spiritual Climate Scores | Respective Employees’ Service Scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.81 | 3.83 | 3.34 | 3.76 |

| 2 | 3.65 | 3.66 | 2.84 | 3.50 |

| 3 | 3.49 | 4.09 | 2.87 | 3.71 |

| 4 | 4.41 | 3.93 | 3.24 | 3.78 |

| 5 | 3.74 | 4.02 | 3.30 | 3.96 |

| 6 | 3.98 | 4.14 | 3.32 | 3.98 |

| 7 | 3.55 | 3.99 | 3.36 | 3.80 |

| 8 | 3.86 | 4.18 | 3.07 | 3.83 |

| 9 | 3.52 | 4.10 | 3.37 | 3.43 |

| 10 | 3.83 | 3.95 | 3.13 | 3.68 |

| 11 | 3.78 | 3.85 | 3.32 | 4.03 |

| 12 | 3.87 | 3.64 | 3.18 | 3.37 |

| 13 | 3.73 | 3.57 | 3.41 | 3.76 |

| 14 | 3.74 | 3.80 | 3.26 | 3.72 |

| Average | 3.78 | 3.91 | 3.21 | 3.74 |

| SD | 0.193 | 0.196 |

Levene’s test of homogeneity of variance tests the assumption that each group (category) of the independent (s) has the same variance on an interval dependent. If the Levene statistic is not significant at the 0.05 level, the null hypothesis that the groups have equal variances cannot be rejected. Significant score of t-test for difference of means support the main hypothesis (H1) that branches showing higher spiritual climate will be experienced by customers as providing better employee service. Findings of t-test further strengthened the assumption that impact of spiritual climate is more pronounced in stream cases.

TABLE VI

Findings of t-test

| t | 2.366 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) p Value | .026 |

| Levene’s Test Sig. | 0.730 |

To check this possibility five highest (H5) and five lowest (L5) branches in terms of spiritual climate were identified. Difference of their combined mean scores of employees service was checked through Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). The following Table VII summarizes the result of ANOVA.

Results of ANOVA showed that impact of spiritual climate is more pronounced in extreme cases.

Discussion

Our paper is aimed to contribute to the relatively sparse, but growing, literature on spiritual aspects of work and its connection with business-related outcome. Our first goal has been to develop a construct of spiritual climate. Spiritual climate was defined as collective perception of the employees’ about the workplace that facilitates harmony with ‘self’ and transcendence and operates in harmony with social and natural environment having interconnectedness within it. Although much is known about the psychological and social aspects of work climate, less is known about spiritual aspects of work and workplace. Following the suggestion of Whetton (1989) our aim was to organize (parsimoniously) and to communicate (clearly) the spiritual climate construct.

TABLE VII Findings of ANOVA

| No. | Sub-construct of spiritual climate | Employees’ Service Score | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H5, n = 76 | L5, n =78 | |||

| 1 | H1a (Meaningfulness) | 3.99** (F 13.004) | 3.66 | Acceptable |

| 2 | H1b (Sense of community) | 3.95** (F 2.28) | 3.74 | Acceptable |

| 3 | H1c (Concern for family) | 3.97 (F 0.5) | 3.91 | Not Accepted |

| 4 | H1d (Authenticity) | 3.94* (F 3.56) | 3.73 | Acceptable |

| 5 | H1e (Loksangrah) | 3.98** (F 14.06) | 3.68 | Acceptable |

| 6 | H1f (Meditative work) | Variable dropped before hypothesis testing | ||

*p value < 0.05; ** p value < 0.001.

Secondly, we hypothesized the positive relationship between spiritual climate and customers’ experience of employees’ service. An important criterion for explanatory potential of the hypothesis is specificity of the substantive nature of relationship between the antecedent and the consequent. Specification of ‘necessary or sufficient’ conditions is called for at this stage. Findings of regression and correlation analysis suggest that linear relationship between the dependent and independent constructs is not very strong. Empirical findings suggest that at least one variable that is the ‘size of the branch’ has also resulted in significant variance on customers’ experience of employees’ service. Other forms of organizational climate that affect the customer service have also been identified in literature (e.g., service climate, psychological climate, etc.). These findings indicate that ‘spiritual climate’ is one of the necessary conditions for better customers’ experience of employees’ service but not the sufficient one. In furtherance to the discussion section we summarize the key theoretical implications of this research.

Theoretical implication

This study is a response to the call of Gupta (1996) for examining if there is any place for the sacred in the organizations and their development. Spirituality is sacred aspect of human self and a form of human potential. For some, it represents highest reach of human development (Wilber, 2004). This study being focused on an aspect of human potential is aimed to contribute toward positive organizational behavior (POB). POB scholars also seek to identify the role of organizational climate and its impact of sustained performance (Roberts, 2006). As mentioned in the review section many positive psychologists like Maslow, Frankl, and Roger indicated toward the human tendencies of search for meaning and purpose in life and opportunity to contribute to their larger social and natural environment. Like most of the POB research this work sharpened the focus of spirituality, a dimension of human potential in organizational context, conceptualized spirituality as climatic variable, and incorporated the generative mechanism of it in the form of employees’ service.

This study draws on positive psychology and aims to carve a broader agenda for how a focus on positive opens up different ways of seeing and understanding organization and people working with them. Most of the existing foundational theoretical perspectives draws on agency cost theory and transactional cost theory of the firm. Transaction cost theory advocates tight monitoring and control of people to prevent ‘‘opportunistic behavior’’ (Williamson, 1975). Agency theory subscribes to the assumptions that managers cannot be trusted to do their jobs, which is to maximize shareholder value (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). Management education in general subscribe to these theories. Although actual theories may not be presented to the students and the executives directly but they learned to subscribe these theories and associated worldviews because these have been in the air, shaping the intellectual and normative order (Ghoshal, 2005).

These theories and world views associated with them had been useful in certain ways but do not capture the full essence of humanness (Ghoshal, 2005). The fact remains that human agents, on one hand demonstrate opportunistic behavior but also on other hand search for meaning and purpose in their work. In business share holders’ value is a sure deliverable (as transaction cost view suggests) but concern for larger social and natural environment can also not be ignored. Rising problem of industrial pollution is largely a result of myopic view of business and its deliverables. Now it is largely recognized fact that sustainable development is possible only through sensible business with a concern for larger good. Business organizations on one hand are sites of production and delivery of material and services but on other hand also site of living where individual meaning and purpose are created, shaped and shared amongst the organizational members.

Spirituality of human self represents the positive aspect of human being which goes beyond opportunity seeking tendencies. Vedanta views human being as ‘Amritasya Putrah’; children of immortality. It views human being as multi potential spiritual entity, seeking meaning in life and a place in the larger schema of existence. This view of human being is an alternate of ‘utility optimizer’ or opportunity seeking view of human being which at best considers human being as a ‘resource’ for meeting business objectives. This study demonstrated that spirituality at work, i.e., harmony with self at work, harmony in social and natural environment and transcendence are meaningful to the employees. These aspects are way beyond the opportunity seeking and utility optimizing behavior of employees. The study also demonstrated within the limitation given below that spirituality at work results in better service to the customers. These findings suggest that spirituality at work and business outcome (customers’ service in this case) cannot only coexist but can be of complementing nature. These findings suggest that positive organizational scholarship in general and spirituality in management in particular can enrich the foundational theoretical discourse in management. This may result in theories which can incorporate the wholesome perspective of individual and organizational realities.

Managerial implication

Findings of this research indicate that facilitating employees to find meaning and purpose in their job can positively impact their service performance. The findings substantiate the observation of Nichols (1994) that creating a sense of meaning and purpose in the job may be the most important managerial task in the twenty-first century. Colvin (2006)in his report on ‘Best Places to Work at America’ also mentioned that these are the places where people find it meaningful to work. This study empirically validates these notions to some extent. Employees may derive meaning out of their job from organizational philosophy, nature of work, organizational policies, leadership, etc. Hence, strategic and leadership issues should be dealt with, keeping in view the human quest for meaning and purpose in life.

Pruzan (2001) suggested that socially responsible behavior of the organization positively affects the service quality. Empirical findings of the current study substantiate this notion and point out that concern for larger social and natural environment amongst the employees is reflected in customers’ perception of service. If employees perceive their work as a means or opportunity to contribute to a higher purpose toward community, society, or mankind, the work climate would be more positive and the customers’ experience should get better.

Schneider et al. (1998) reasoned that specific strategic climates are unlikely to achieve the intended outcomes unless they are built on a strong foundation of generic work-facilitation climate. Spiritual climate is one of the generic climates on which other strategically important climate (service climate, transfer of training climate, innovation climate, etc.) can be built.

Research findings may be useful for Organizational Development (OD) work which aims at creating performance-oriented and humanistic culture. OD efforts can facilitate employees and leaders to find meaning and purpose in their work. Developmental work in the organization should include the efforts for building authenticity, sense of community at workplace for better performance and results.

Limitations

At the level of conceptualization, this study is limited in terms of the number of wisdom traditions it surveys. The study largely refers to Vedantic traditional wisdom. Acknowledged here is that this is but one of the many wisdom traditions evolved in different cultures across the world.

This study was conducted in the positivist paradigm with usual limitations of survey research design. This design is suitable for bringing out commonality amongst the respondents and leaves out the uniqueness of the social objects being studied.

This study is limited by its objectives and scope and does not accommodate the aspect of person– organization fit. The study does not explain the situation where persons working in the organization have a higher level of spirituality than the organization and eventually do not find it meaningful to work with the particular organization.

The nature of causal relationship has not been specified in the current study. Like most of the theories in social sciences, we were also prone to concern with recursive causal relation and have not been able to look at plausible teleological, dialectical, or reciprocal causal linkage.

In terms of actual empirical form of relationship, this study informs that the possibility of linear relationship between the antecedent and the consequent is bleak, but it does not inform about the exact form of relationship (curvilinear, or J-curve). Future studies can redress this limitation.

Notes

* Ashish Pandey is Doctoral Fellow of M.D.I., Gurgaon, India and currently leading research and development function at Pragati Leadership Institute Pvt. Ltd., Pune, Maharastra, India.

Rajen K. Gupta is Professor of OD with M.D.I., Gurgaon. He is an OD consultant, alumnus of Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur and holds doctoral degree from Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, India.

A. P. Arora is Professor of Marketing Research with M.D.I., Gurgaon. He has been consultant to more than 30 organization in the areas of branding, cyber marketing etc. He holds doctoral degree from Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, India.

This work is based on the first author’s dissertation. Different parts of this work won Best Paper Award at different international forums held at Indian Institute of Sciences, Banglore and Indian Institute of Management, Indore.

1 Western perspectives of health emanate chiefly from the philosophies of elementalism and humanism (Charlene, 1996). The philosophy of elementalism espoused that human functioning can be divided into separate components. Within this belief system the parts are seen as functioning separately from the whole. In this system illness within one component is treated without regard to the other components, whereas humanism advocates for holistic view of health.

2 According to Sigmund Freud, religion and spirituality are essentially products of wish fulfillment and fantasy. Children seek relief from the ‘‘terrifying impression of helplessness in childhood’’ (Freud, 1927/ 1961 , in Zinnbauer et al., 1999) and need a figure in their lives to protect them. This role of protector is initially provided by one’s own father, but as one grows older and this sense of helplessness continues, the individual needs a more powerful protector. This powerful protector is sought by the individual through a belief in a Divine Father.

3 Vedanta is a spiritual tradition and school of philosophy, largely subscribed in Hindu tradition and is based on the teachings of the Upanishads and is, like those manuscripts, concerned with the self-realisation by which one understands the ultimate nature of reality.

4 Bhagavad Gita, The Song of God, is culmination and extraction of Vedantic wisdom tradition and world’s major spiritual and philosophical literary work, often referred to in the West as the ‘Gospel’ of India. It is considered to be part of the 2-5,000-year-old epic Mahabharata.

5 ‘‘When human being work together in organization harmoniously with their talent and in spite of their distinctiveness, in interdependent and interconnected way it is witness to a visible manifestation of ‘God’’’ (Follett, 1918).

6 Grace and O’Cass (2004) based on the responses from the bank consumers demonstrated that service consumption experience is significantly contributed by three factors: (1) Core service: In the case of banks interest rate, terms and conditions for different services, etc. directly affect the customers’ service experience and are parts of core service. Customers experience the core service in context of suitability of their needs, (2) Servicescape: Servicescape provides valuable tangible brand clues prior to purchase and important dimension of the service experience, (3) Employee service: Employee service is derived from the interactions of employees with customers.

7 http://www2.chass.ncsu.edu/garson/pa765/factor.htm

8 In oblique rotation, one gets both a pattern matrix and a structure matrix. The structure matrix is simply the factor loading matrix as in orthogonal rotation, representing the variance in a measured variable explained by a factor on both a unique and common contributions basis. The pattern matrix, in contrast, contains coefficients which just represent unique contributions. The more the factors, the lower the pattern coefficients as a rule since there will be more common contributions to variance explained.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Prof. Naganand Kumar at M.D.I. (Gurgaon) for insightful discussions held with him.

Annexure

Total variance explained in CFA

Factor |

Initial Eigenvalues |

Extraction sums of squared loadings |

Rotation sums of squared loadings(a) |

||||

Total |

% of Variance |

Cumulative % |

Total |

% of Variance |

Cumulative % |

Total % |

|

1 |

5.829 |

36.434 |

36.434 |

5.434 |

33.962 |

33.962 |

3.670 |

2 |

1.674 |

10.462 |

46.897 |

1.260 |

7.874 |

41.835 |

3.374 |

3 |

1.480 |

9.250 |

56.147 |

1.154 |

7.211 |

49.046 |

3.215 |

4 |

1.199 |

7.496 |

63.643 |

0.780 |

4.875 |

53.921 |

2.959 |

5 |

1.077 |

6.731 |

70.374 |

0.748 |

4.677 |

58.598 |

1.874 |

6 |

0.842 |

5.261 |

75.635 |

||||

7 |

0.681 |

4.258 |

79.893 |

||||

8 |

0.624 |

3.903 |

83.796 |

||||

9 |

0.464 |

2.900 |

86.697 |

||||

10 |

0.428 |

2.677 |

89.374 |

||||

11 |

0.369 |

2.304 |

91.678 |

||||

12 |

0.339 |

2.119 |

93.797 |

||||

13 |

0.305 |

1.903 |

95.701 |

||||

14 |

0.271 |

1.696 |

97.397 |

||||

15 |

0.251 |

1.566 |

98.963 |

||||

16 |

0.166 |

1.037 |

100.000 |

||||

References

Addis, L.: 1995, ‘Holism’, in R. Audi (Gen. edi.), The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy (Cambridge University Press, New York), pp. 335–336.

Anderson, N. R. and M. A. West: 1998, ‘Measuring Climate for Work Group Innovation: Development and Validation of the Team Climate Inventory’, Journal of Organizational Behavior 19, 235–258.

Ashforth, B. E. and M. G. Pratt: 2003, ‘Institutionalized Spirituality: An Oxymoron?’, in R. A. Giacalone and

C. L. Jurkiewicz (eds.), Handbook of Workplace Spirituality and Organizational Performance (M.E. Sharpe, New York), pp. 93–107.

Ashmos, D. P. and D. Duchon: 2000, ‘Spirituality at Work: A Conceptualization and Measure’, Journal of Management Inquiry 9(2), 134–146.

Assadourian, E.: 2006, ‘Transforming Corporations’, in

S. Linda (ed.), State of the World, Worldwatch Institute Report on Progress Toward a Sustainable Society (W. W. Norton & Company, New York), pp. 171–189.

Bacharach, S. B.: 1989, ‘Organizational Theories: Some Criteria for Evaluation’, Academy of Management Review 14(4), 496–515.

Basadur, M.: 1992, ‘Managing Creativity: A Japanese Mode’, Academy of Management Executive 6(2), 29–42.

Benefiel, M.: 2003, ‘Mapping the Terrain of Spirituality in Organizations Research’, Journal of Organizational Change Management 16(4), 367–377.

Bensley, R. J.: 1991, ‘Defining Spiritual Health: A Review of the Literature’, Journal of Health Education 22(5), 287–290.

Bhattacharya, K.: 1995, ‘Vedanta as Philosophy of Spiritual Life’, in K. Sivaraman (ed.), Hindu Spirituality: Vedas Through Vedanta (Motilal Banarsidass, New Delhi).

Biberman, J. and M. Whitty: 1997, ‘A Post Modern Spiritual Future for Work’, Journal of Organizational Change Management 10(2), 130–138.

Carlzon, J.: 1997, ‘Putting the Customer First: The Key to Service Strategy’, The McKinsey Quarterly, Summer.

Chandon, J. L., P. Y. Leo and J. Philippe: 1997, ‘Service Encounter Dimensions – A Dyadic Perspective: Measuring the Dimensions of Service Encounter as Perceived by Customers and Personnel’, International Journal of Service Industry Management 8(1), 65–86.

Charlene, W. E.: 1996, ‘Spiritual Wellness and Depression’, Journal of Counseling and Development 75(1), 26–36.

Chatman, J. A. and S. Barsade: 1995, ‘Personality Organizational Culture and Cooperation: Evidence from a Business Simulation’, Administrative Science Quarterly 40(3), 423–443.

Cho, H. J. and V. Pucik: 2005, ‘Relationship Between Innovativeness, Quality, Growth, Profitability and Market Value’, Strategic Management Journal 26(6), 555–575.

Colvin, G.: 2006, ‘The 100 Best Companies to Work’, Fortune 1, 50.

Cronbach, L. J.: 1951, ‘Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests’, Psychometrika 16, 297–334.

Crosby, L. A., K. R. Evans and D. Cowles: 1990, ‘Relationship Quality in Services Selling: An Interpersonal Influence Perspective’, Journal of Marketing 54(7), 68–81.

Dehler, G. E. and M. A. Welsh: 1994, ‘Spirituality and Organizational Transformation’, Journal of Managerial Psychology 9(6), 17–24.

Dent, E. B., M. E. Higgins and D. Wharff: 2005, ‘Spirituality and Leadership: An Empirical Review of Definitions, Distinctions, and Embedded Assumptions’, Leadership Quarterly 16(5), 625–653.

Drexler, J. A. Jr.: 1977, ‘Organizational Climate: Its Homogeneity with Within Organization’, Journal of Applied Psychology 62, 38–42.

Dunn, H. L.: 1961, High Level Wellness (R. W. Beatty, Arington, VA).

Fineman, S.: 1993, ‘Organizations as Emotional Arenas’, in S. Fineman (ed.), Emotion in Organizations (Sage, Newbury Park, CA), pp. 9–35.

Fischer, K.: 1988, Women at the Well: Feminist Perspective on Spiritual Direction (Paulist, New York).

Follett, M. P.: 1918, The New State: Group Organization and The Solution of Popular Government (Longmans, Green, and Co., London).

Frankl, V.: 1978, The Unheard Cry for Meaning (Simon & Schuster, New York).

Freud, S.: 1961, ‘The Future of an Illusion’, in J. Strachey (ed. and Trans.), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 11 (Hogarth Press, London), pp. 5–56. Original work published 1927, in Zinnbauer B. J., K. I. Pargament and A. B.

Fromm, E.: 2003, On Being Human (Continuum, New York).

Fry, L. W.: 2003, ‘Towards the Theory of Spiritual Leadership’, Leadership Quarterly 14, 693–727.

Ghoshal, S.: 2005, ‘Bad Management Theories are Destroying Good Management Practices’, Academy of Management Learning & Education 4, 75–91.

Giacalone, R. A. and C. L. Jurkiewicz: 2003, ‘Right from Wrong: The Influence of Spirituality on Perceptions of Unethical Business Activities’, Journal of Business Ethics 46(1), 85–94.

Grace, D. and A. O’Cass: 2004, ‘Examining Service Experience and Post-Consumption Evaluation’, Journal of Service Marketing 18(6), 450–461.

Gupta, R. K.: 1996, ‘Is There a Place for the Sacred in Organizations and Their Development’, Journal of Human Values 2(2), 149–158.

Harris, M.: 1989, Dance of the Spirit: The Seven Steps of Women’s Spirituality (Bantam, New York).

Heaton, D. P., J. Scmidt-Wilk and F. Travis: 2004, ‘Construct, Method, and Measures for Researching Spirituality in Organizations’, Journal of Organizational Change Management 17(1), 62–82.

Henson, R.: 2003, ‘HR in the 21st Century’, in

R. Henson (ed.), Headcounts (People Soft), pp. 257–269.

Hofmann, D. A. and A. Stetzer: 1996, ‘A Cross Level Investigation of Factors Influencing Unsafe Behavior and Accidents’, Personnel Psychology 49, 307–339.

Howard, S.: 2002, ‘A Spiritual Perspective on Learning in the Workplace’, Journal of Managerial Psychology 17(3), 230–242.

Ingersoll, R. E.: 2003, ‘Spiritual Wellness in the Workplace’, in R. A. Giacalone and C. L. Jurkiewicz (eds.), Handbook of Workplace Spirituality and Organizational Performance (M.E. Sharpe, New York), pp. 289–299.

Jensen, M. and W. Meckling: 1976, ‘Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure’, Journal of Financial Economics 3, 305–360.

Jung, C. G.: 1933, Modern Man in Search of a Soul (Harcourt, Brace, New York) in Charlene, 1996.

Jung, C. G.: 1978, ‘Psychological Reflections, Princeton’, NJ: Bollingen. in A. M. Keating and B. R. Fretz: 1990, ‘Christian Anticipations About Counselors in Response to Counselor Descriptions’, Journal of Counseling Psychology 36, 292–296.

Jurkiewicz, C. L. and R. A. Giacalone: 2004, ‘A Values Framework for Measuring the Impact of Workplace Spirituality on Organizational Performance’, Journal of Business Ethics 49(2), 129–142.

Kalra, S. K.: 1997, ‘Human Potential Management: Time to Move from Concept of Human Resource Management’, Journal of European Industrial Training 21(5), 176–180.

Kinjerski, V. M. and B. J. Skrypnek: 2004, ‘Defining Spirit at Work: Finding Common Ground’, Journal of Organizational Change Management 17(1), 26–42.

Krishnakumar, S. and C. P. Neck: 2002, ‘The ‘‘What’’, ‘‘Why’’, and ‘‘How’’ of Spirituality in the Workplace’, Journal of Managerial Psychology 17(3), 153–164.

Larson, R. W.: 2000, ‘Toward a Psychology of Positive Youth Development’, American Psychologist 55, 170–183.

Lips-Wiersma, M.: 2003, ‘Making Conscious Choices in Doing Research on Workplace Spirituality: Utilizing the ‘‘Holistic Development Model’’ to Articulate Values, Assumptions and Dogmas of the Knower’, Journal of Organizational Change Management 16(4), 406–425.

Luthans, F. and A. Church: 2002, ‘Positive Organization Behaviour: Developing and Managing Psychological Strengths’, Academy of Management Executive 16(1), 57–75.

Marcqus, J., S. Dhiman and R. King: 2005, ‘Spirituality in the Workplace: Developing an Integral Model and a Comprehensive Definition’, Journal of American Academy of Business 7(1), 81–92.

Marques, J.: 2005, ‘Redefining the Bottom Line’, The Journal of American Academy of Business, Cambridge 7(1), 283–287.

Maslow, A. H.: 1968, Towards a Psychology of Being (Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York).

Maslow, A. H.: 1971, Farther Reaches of Human Nature (Viking, New York).

Maslow, A. H.: 1996, ‘Higher Motivation and New Psychology’, in E. Hoffman (ed.), Future Visions: The Unpublished Papers of Abraham Maslow (Sage, Thousand Oaks).

McCormick, D. W.: 1994, ‘Spirituality and Management’, Journal of Management Psychology 9(6), 5–8.

Milliman, J. F., A. J. Czaplewski and J. M. Ferguson: 2001, An Exploratory Empirical Assessment of the Relationship Between Spirituality and Employee Work Attitude. Academy of Management Proceedings, Washington DC.

Mirvis, P. H.: 1997, ‘‘‘Soul Work’’ in Organizations’, Organization Science 8(2), 193–206.

Mitroff, I. I. and E. A. Denton: 1999, A Spiritual Audit of Corporate America: A Hard Look at Spirituality, Religion, and Values in the Workplace (Jossey-Bass, San Francisco).

Morgan, J. D.: 1993, ‘The Existential Quest for Meaning’, in K. J. Doka and J. D. Morgan (eds.), Death and Spirituality (Baywood, Amityville, NY), pp. 3–9.

Moxley, R. S.: 2000, Leadership and Spirit (Jossy-Bass, San Francisco, CA).

Nichols, M.: 1994, ‘Does New Age Business have a Message for Managers?’, Harvard Business Review 72(2), 52–60.

Nicholls, J. A. F., R. G. Gilbert and S. Roslow: 1998, ‘Parsimonious Measurement of Customer Satisfaction with Personal Service and the Service Setting’, Journal of Consumer Marketing 15(3), 239–253.

Nonaka, I. and H. Takeuchi: 1995, The Knowledge Creating Company (Oxford University Press, New York).

Nur, Y. A.: 2003, Management by Virtues: A Comparative Study of Spirituality in the Workplace and Its Impact on Selected Organizational Outcomes. Unpublished PhD Dissertation in Proquest database, Indiana University, USA.

Pandey, A. and R. K. Gupta: 2008, ‘Spirituality in Management: A Review of Traditional and Contemporary Thoughts’, Global Business Review 8(1), 65–83.